Kuna Indian Textile Art from the San Blas Islands of Panama

Molas for sale are posted in the different Galleries

The Kuna (or Guna) Indians are the indigenous people who live on small coral islands in the San Blas Archipelago along the Atlantic coast of Panama and Colombia. They were driven westward in the 16th century from their original home in Colombia by invading Spanish colonizers and similar migrations of other Indian tribes, notably the Wounaan and Embera. They first moved into the Darien Rainforest, then towards the coastal Mainland of Panama, and by the 19th century they had begun to move out to the islands where they now live in the semi-autonomous region called Yala Guna.

What is a Mola?

Mola, which originally meant bird plumage, is the Kuna Indian word for clothing, specifically blouse, and the word mola has come to mean the elaborate embroidered panels that make up the front and back of a Kuna woman's traditional blouse. The vibrant reds of the traditional mola have entranced fashion designers and are often found as bright accents in the home. Molas are collected as folk art: Kuna women have achieved a worldwide reputation for outstanding artistry.

|

What is the origin of a mola, the traditional Kuna blouse?

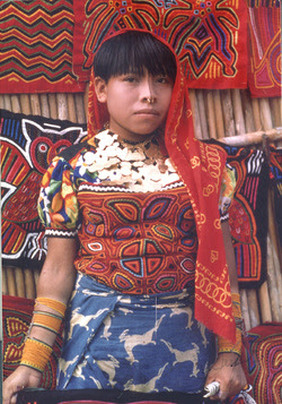

The first references to “Cuna” women in the early 16th century described them as paying careful attention to their appearance with elaborate body painting, wearing skirts of pounded bark, multiple necklaces that covered their bare breasts, and a ring in their nose. By the mid-18th century, cloth was introduced by European settlers, and women eventually started wearing a cloth blouse which they began to paint in the same way they had painted their upper bodies, with indigo from jagua juice, red from annatto juice, and yellow from turmeric root. How is a mola made? Reverse appliqué has been used to make a mola since Victorian times. A mola maker places two or three pieces of different colored cloth on top of each other and bastes them together. Then she cuts into the top layer, cutting out her design (she may have drawn her design first in pencil, but often she just follows the idea in her head.) Only the bottom layer remains intact to be the background color and support the stitching of the other pieces. She hems all the cut edges with very fine stitches, making sure that her thread exactly matches the color of the cloth. The color of each lower level creates the outline of the design. She may then add additional elements - decorative embroidery, positive appliqué, slits showing different colors from cloth that has been inserted between layers - to complete these intricate designs. What makes a good traditional mola? The principal design should be immediately recognizable. It should not be confused by additional added elements or colors. When studied from three to six feet away, the same way one appreciates a painting, the mola should be harmonious in color with a balanced design. The entire panel should be filled. Traditional designs are geometric patterns, subjects inspired by nature, animals, fish, flowers, and daily life. The artist will always add her personal touch, and subjects of acculturation can be interesting and sometimes amusing. When presented together or as a blouse, the two mola panels should look very much alike and differ only in small details of design and color. “They should be the same but different,” say the Kuna. The stitches should almost be invisible; the thread should be exactly the same color as the fabric and the stitches small and close together. The curves of the designs should be very smooth and not a series of straight lines. Once they have been hemmed, all the colored lines that form the design (the cut out edges) should be straight and very even in width (1/8” to 3/32” maximum). The entire surface of the mola should be used, but the filler elements, slits, positive appliqué figures, triangles, rounds, and additional embroidery, should highlight the main subject and not overwhelm it. When laid flat, the mola should not be uneven. Good quality fabric should be used. A good, traditional mola takes three to five weeks to sew, and sometimes longer for exceptionally fine pieces. What designs are most popular? When the Kuna began wearing cloth blouses, the designs were primarily geometric patterns taken from their body decorations or else inspired from nature or daily life. Abstract patterns were popular, too, as were depictions of birds, fish, sea creatures, flowers, scenes of daily life, household implements, and occasionally symbolic or mythological subjects. When U.S. engineers (merki) came to build the Panama Canal in 1904, elements of acculturation from the outside world began to creep into mola design from newspapers, films, television programs, and tourists. Modern mola makers often take their inspiration from older designs and invent new ones, sometimes combining abstract patterns with a representational subject. Modern molas have become very elaborate. Changes in Molas Early molas were big, and descended below the knees. The large designs were fairly simple but not always symmetrical, the stitches were somewhat uneven, and the thread did not necessarily match the color of the cloth. A heavier cotton fabric was used and four or five layers of cloth were the norm. These molas are antiques, often faded from use and washing, and show the signs of having been part of a blouse. As time went on, the cloth used and the size of the molas evolved. Today the blouse is worn tucked into the skirt and the smaller mola panel measures on average 12” x 16”. The Kuna used percale imported from England for many years, but they now use mercerized cotton or poplin from Colombia or Asia. A Kuna woman will make herself a new mola for special ceremonies, and she will usually wear her traditional dress every day – a headscarf (muswe), mola blouse, wrap-around skirt (saboured) of dark blue or green with a subdued pattern, wrappings of beads (wini) around her calves and arms, and a black painted stripe of jagua juice down her nose which calls attention to her gold nose ring. Kuna women are proud of the fineness of their stitches, the exact color match of their thread, the complexity of their design. A woman will spend several hours each day sewing and young girls begin creating “molitas”, little molas, by the time they are six or seven. Since tourists usually want to buy only the mola panels, the Kuna now also make molas never intended for a blouse. These “tourist molas” usually have only two layers of cloth with positive appliqué and embroidery. They are often in vivid colors, frequently portray birds, and take only a few days to sew. Some, however, are extremely intricate and can include several layers of fabric with reverse appliqué. Some are even large enough to be tapestries or wall hangings. The exhibit, “ Textile Art: Kuna Indian Molas from Panama” at the Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center in Phoenix, Arizona shows the changes in the art of sewing molas as they have developed from the fairly simple patterns of early 20th century blouses to today’s more sophisticated and elaborate mola panels designed not as clothing but specifically for tourists. The January and February 2013 exhibit is curated by Dr. Margo Callaghan who has been collecting Kuna Indian molas from Panama since the early 1970’s. References: Edith Crouch, The Mola: Traditional Kuna Textile Art. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2011. Capt. Kit S. Kapp, Mola Art from the San Blas Islands. Cincinnati: Kit. S. Kapp Publications, 1972. Michel Lecumberry, San Blas: Molas and Kuna Traditions. 2nd Revised Edition. Translated by Margo M. Callaghan. Panama: Txango Publications, 2006. Michel Perrin. Magnificent Molas: The Art of the Kuna Indians. Paris: Flammarion, 1998. Mari Lyn Salvador, The Art of Being Kuna: Layers of Meaning among the Kuna of Panama. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1997. |

Photo of Guna girl by Anita Seifert. (below)

|